Conflict Intelligence (CIQ)

Conflict Intelligence (CIQ) is essentially the capacity to do the right thing at the right time in response to very different conflicts. It begins with the recognition that in the current volatile, often-politicized environment, there is no one-size-fits-all approach to managing different types of conflicts effectively. So, it is crucial to have alternate strategies for responding to distinct disputes and to know which option best “fits” which situation. This means moving beyond standard win-win versus win-lose choices of conflict management toward mastering more adaptive, situationally-appropriate approaches.

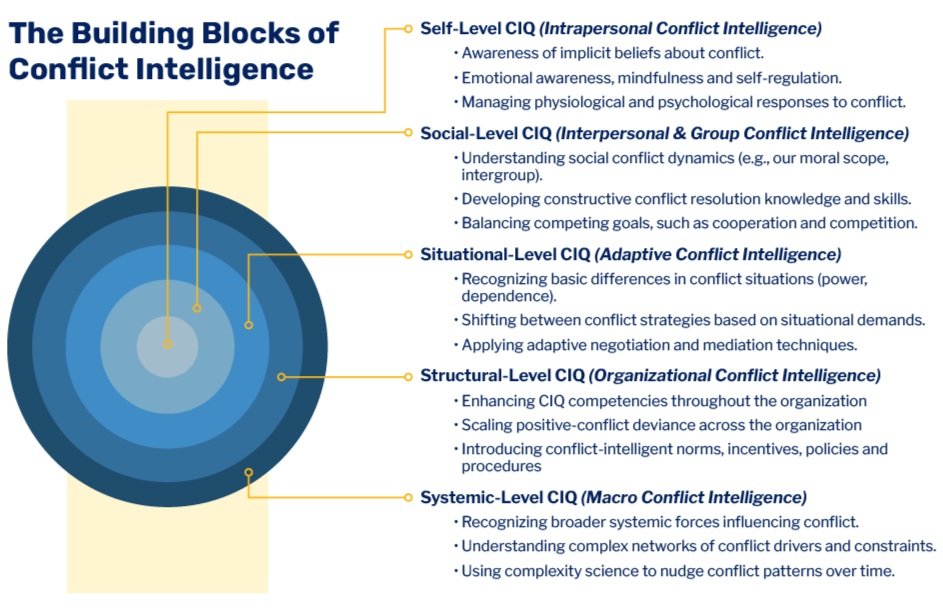

The development of CIQ requires a broadening of one’s orientation to conflict across four levels: from a focus on and awareness of the self (implicit beliefs, emotional reactions, and ability to self-regulate), to a focus on social dynamics (interpersonal, intergroup, and moral conflict dynamics), as well as situational dynamics (conflicts in fundamentally different contexts), and ultimately to a focus on the broader systemic forces that may determine and be determined by more entrenched conflicts.

4 Core Assumptions

At its core, CIQ is based on four empirically-derived assumptions:

Conflict is a natural and necessary element in life. Conflict is a pervasive, naturally-occurring aspect of life that is an essential source of energy for learning (Deutsch, 1973; Johnson & Johnson, 1979), relationship enhancement (Gottman et al., 2014), creativity (Coleman & Deutsch, 2014), innovation (Tjosvold & Wong, 2010), and equitable societal reform (Coleman et al., 2022);

Conflict initially feels bad. Conflict often automatically triggers negative associations and experiences due to our hard-wired sensitivity to perceptions of threat (neurological) (Cikara et al., 2014), primitive unconscious fears (psychological) (Deutsch, 1993), and the fact that it tends to initially tax our energy levels (metabolic) (Barrett, 2017);

Conflicts add up emotionally over time. Our experience of conflicts in particular situations and relationships is accumulative and formative (Gottman et al., 2014) – establishing reservoirs of positivity and negativity that shape our reactions in those situations.

Our first responses to conflict are crucial. How conflicts are initially reacted to (Kugler & Coleman, 2020) and managed (Coleman & Chan, 2023) are critical determinants of whether their energy brings a higher ratio of positive-to-negative consequences.

The Anatomy of CIQ

The Anatomy of Conflict Intelligence: 5 Steps to a Higher CIQ

Research has identified a set of core competencies for increasing CIQ (Coleman, 2018), which involve five nested levels of experience:

The Value of CIQ

Managing Contradictions

Recognizing that our current world often presents us with conflict scenarios filled with contradictions, tough trade-offs, and dilemmas (I really need this staff member and they drive me nuts), one CIQ technique encourages alternating, intentionally and strategically, between seemingly contradictory responses to conflict. Such responses include competing and cooperating (Liebovitch et al. 2008), escalating and de-escalating tension (Coleman et al. 2017), being self-focused and other-focused (Kim and Coleman 2015), and exploring common interests and advocating bottom-line positions (Kugler and Coleman 2020), and doing so in a manner that seeks optimal ratios of responses that help to manage trade-offs.

Adapting Fittingly

Building on classic research on contingency approaches to dispute resolution (Walton and McKersie 1965), this class of CIQ models begins by identifying the most defining aspects of different types of conflict situations (see Wish et al. 1976), and then offers a series of distinct strategies that have been found to be the most fitting and effective in each. Adaptivity is defined as the capacity to adapt to distinct or changing situations, but in a manner that maintains the integrity of the needs and interests of the conflict resolver (Mitchinson et al. 2009). We have developed approaches to adapting to conflicts across significant power and relational differences at work—as seen in Making Conflict Work (2014)—when helping to mediate conflicts in more extreme, “derailing” situations (Coleman and Flax 2022), and for navigating disputes across profound cultural differences effectively (Phan and Coleman 2023).

Locating Hidden Levers for Change

The CIQ approach starts with the premise that more chronic, demanding conflicts are rarely caused by one thing, and the longer they last the more likely they are fed by an increasingly broad constellation of drivers and constraints (Coleman 2011a). Therefore, it is often useful to begin with a listing and mapping of the cloud of forces driving and constraining these tensions at the local (and therefore more actionable) level (Coleman et al. 2019).

Playing the Long Game

When longer-term, high-intensity conflicts appear to become stuck in repetitive, destructive patterns, despite the desire of the disputants to escape them and good-faith attempts to resolve them by capable intermediaries, they are thought to have become trapped by an attractor dynamic. Attractors are relatively stable, multiply determined patterns that emerge in systems (people, relationships, organizations, communities) slowly over time, but, across some threshold, can become very hard to change but very easy to lapse into (Vallacher et al. 2010b). Think of them like an advanced addiction or unruly obsession, which, despite the adverse consequences they bring to our health, livelihood, and relationships, draw us into destructive patterns of behavior again and again, leading ultimately to catastrophe. When strong attractors capture a conflict dynamic (Coleman 2011), it becomes necessary to pivot attention away from the presenting conflict episodes and toward the surrounding context of forces fueling them over time.